Perhaps the most common, and certainly the most conspicuous, butterfly in South Florida in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was the Atala Blue butterfly, Eumaeus atala.

It is a dietary specialist, relying on the leaves of a cycad, coontie (Zamia integrifolia, formerly/also known as Z. pumila) for its larval nutrition. Like many cycads, coonties contain high levels of a type of protein (a glucoside known as cycasin), which is fairly toxic, along with many other nasty flavones, vicilin-like seed proteins, alkanes in the foliar waxes, azoglucosides, and nonprotein amino acids (that long list of things I don’t understand comes from Dan Austin’s magisterial and much-loved Florida Ethnobotany listed in the references section, and you can look up all the source details there, if you’re interested).

With a bit of ingenuity, though, humans are able to process the poisonous but starchy coontie roots into an edible flour (arrowroot, although coontie was only one of several sources of it). The original Native Americans in south Florida, the Timucuans and Calusas, certainly knew how to use it. And according to Culbert, “Spanish writings from the sixteenth century report that [the natives] removed the toxic chemical, cycasin, from the coontie stem by maceration and washing.” And the Seminoles who eventually displaced them apparently picked up this technique.

Arrowroot flour derived from the coontie stem was a great resource, since it was resistant to the molds that would otherwise thrive on flour in these humid environs. That made coontie flour much more useful in pre-air-conditioning Florida than the delicate wheat flours we’re used to these days. In fact, according to Richard Levine, coontie flour was so useful that “it was simultaneously sold during the Indian-American Wars to both the Indians and the U.S. Army,” and was even exported to Europe as a gourmet flour.

That all ended in 1925 when the USDA banned the use of coontie in the production of arrowroot flour. So now we get our arrowroot from other plants:

Coontie plants were so numerous along the banks of a certain river here in south Florida that back in the 1830s a plantation grew up that eventually grew into the city of Fort Lauderdale! The river was known to the Seminoles as coonte hatchee, or coontie water, but we English-speaking settlers just call it the New River. And although the plantations were all destroyed after just a couple of years (among the events that led to the second Seminole War, actually), William Lauderdale and his Tennessee Volunteers built the fort (yes, that fort, Fort Lauderdale) on the same site that formerly housed the plantations.

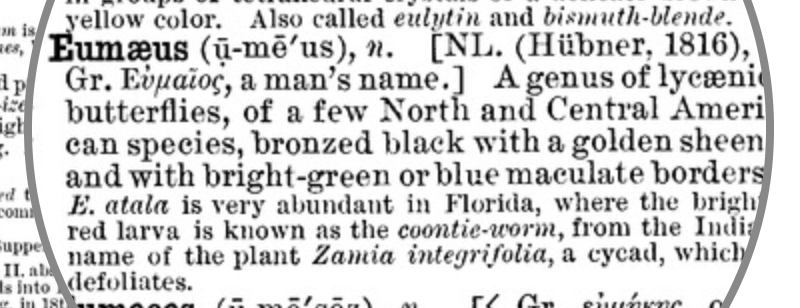

How abundant were the butterflies that coexisted (indeed, in a fairly symbiotic relationship) with the coontie? So numerous that in the Century Dictionary (last publication date 1914 but so well-loved that the entire text has been put online), under the genus name (Eumaeus), E. atala are the only exemplar, and they are described as “very abundant in Florida”:

Unfortunately, that dictionary is a bit out of date. Coonties, like most cycads, are relatively slow growing, so it’s fairly hard to sustain any level of industrial agricultural exploitation, and despite coontie plantations being reestablished after the Seminole wars, the level of consumption far outstripped sustainable population levels. Despite the USDA ban on the use of coontie in the production of arrowroot flour, the plant was almost extirpated.

Given that the coontie plant was this butterfly’s only food source, once the plants grew scarce, the population of the Atala blue plummeted, to the point that the insect was believed to be extinct in the 1930s, with occasional sightings lasting into the 1960s. Then in 1979, a population from a Miami county barrier island served to restore the butterfly to a wider area in which the hardy native (the only cycad native to North America) had begun to be replanted in native gardens.

Ecology

The ecological relationship in a coontie garden/plantation is at least a three-way symbiosis. Cycads are not flowering plants; they rely on wind or animals to transfer pollen from the male plants to the females (they are dioecious, meaning that there are male plants and female plants). In the case of coontie, the plants are pollinated by a couple of relatively nonphotogenic weevils (and apparently it’s unusual, that it’s not a single specialist species; see Constantino’s article in the reference list; it provides some good background information on propagating coonties).

The coontie is pollinated by weevils. So why does it need the butterflies? It offers, rather generously one might imagine, nutrients and defensive chemicals to the butterfly. And in return, the larvae of the Atala blue sometimes (often, at least nowadays) eat the plant’s leaves all the way to the ground! (Lots of native gardeners tell me what a pest the Atala blue can be!)

What does the butterfly offer the cycad? (In other words, why do we view their relationship as symbiotic, rather than parasitic?) The answer, of course, is frass. Poop. Lots of larvae means lots of eating, and lots of eating means lots of pooping. And all that poop cycles the nutrients from the plant back to the soil and back into the plant!

Since the larvae will often literally eat themselves out of house and home, and their home is in a dynamic environment, the population is subject to boom-and-bust cycles. As described by Koi and Daniels, “individual colonies or subpopulations are highly ephemeral as seasonal or abnormal weather events occur. Overall population dynamics demonstrate periodic and somewhat unpredictable crash–eruption cycles.”

It is not listed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as needing any special protection, although it was considered “Near Threatened” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources as recently as 2012 (it is no longer on their red list as of this writing). And since much of its current population lives in highly fragmented habitat (individual homes with coonties, which could disappear as landscape preferences change or homes change hands), it could face an uncertain future.

Butterfly Life Cycle

Like all butterflies, the Atala is holometabolous, meaning it has four life stages: egg, larva, pupa, adult. In the picture below, the last stage is installing the first stage in the proper environment, viz. the underside of a new leaf of its host plant.

Since the eggs were laid just yesterday, I’m really looking forward to seeing whether I can see when they eclose (geek speak for “hatch); the typical time is about a week, but it can be anywhere from 4 to 14 days. Once they do, of course, the second, or larval, phase of the life cycle will begin.

The larvae (more commonly called “caterpillars”) will go through several instars (“stages”), eventually acquiring this gorgeous red and yellow aposematic (“warning”) coloration, as seen here in a couple of shots from years past:

After they’ve obtained enough nutrients (and toxins!) from their cycad-exclusive diet, the caterpillars begin the third phase of their life cycle: they pupate

And, then, of course, the cycle begins anew when the adults emerge transformed yet again into the lovely fourth stage. The shots below are taken from my archives here on benkolstad.net, since yesterday’s butterfly, while very patient (she was there for quite a long time), was not in a position that lent itself to the comfort of the photographer.

Etymology

Atala: (1) A bicycle company and racing team from the early 1900s to the late 1980s. Pretty nifty machines, and they came in blue!:

Atala (2) The Indian princess of Chateaubriand’s early nineteenth-century novella set in America, Atala, ou Les Amours de deux sauvages dans le désert. Presumably it’s this version that prompted Poey to name the Atala butterfly back in 1832, as bicycle racing, indeed the bicycle itself, was not yet a thing.

Coontie: According to Austin, a Seminole word meaning “edible roots.” First applied to plants in the genus Smilax but later used for Zamia integrifolia after the Seminoles encountered the plant in south Florida. Smilax roots were “red coontie”; Zamia roots were “white coontie.”

Eumaeus was the swine herder and friend of Odysseus, hero of the Trojan War in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.

Zamia has an obscure etymology. Dan Austin writes that it comes either from azaniea nueces, “dried-up nuts,” or from the Latin zamia or samia, “to hurt or damage.” Integrifolia is a technical term meaning the plant has “entire leaves” (a smooth margin with no teeth, notches or other textures along the edge). Only a true taxonomist would describe the highly textured leaves of a coontie plant as “entire.”

Selected References

Austin, Daniel. Florida Ethnobotany. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2006.

Constantino, Art, with Introductory Comments by Sandy Koi, Janice Malkoff, and Peggy Strumski. “Propagation and Growing Coonties.” Available at: http://browardbutterflies.org/Coontie%20Background%20Information.pdf

Culbert, Daniel F. “Florida Coonties and Atala Butterflies.” ENH117, originally published October 1995. Revised March 2010. Reviewed September 2016. Available at: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/MG/MG34700.pdf.

Koi, Sandy, and Jaret Daniels. Florida Entomologist 98, no. 4, 2015. Available at: https://bioone.org/journals/Florida-Entomologist/volume-98/issue-4/024.098.0418/New-and-Revised-Life-History-of-the-Florida-Hairstreak-Eumaeus/10.1653/024.098.0418.full

Levine, Richard. “A Nearly Extinct Butterfly Makes a Comeback in South Florida.” Entomology Today, March 21, 2016, https://entomologytoday.org/2016/03/21/a-nearly-extinct-butterfly-makes-a-comeback-in-south-florida/

1 thought on “Atala Blues”