The senna plants I put in this spring have been paying dividends for the last couple of months already. A nearly constant population of Cloudless Sulphur (Phoebis sennae) butterflies has been present, both adults and caterpillars, although the former are quite a bit more difficult to photograph than the latter. Still, I’ve managed a few decent shots.

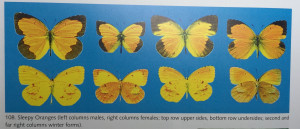

This month (October, for those of you who aren’t reading this the instant I post it) these plants brought in a new species to the yard: Sleepy Orange, Eurema nicippe. I knew it wasn’t a Cloudless Sulphur right away, because it was quite a bit smaller, and the upper side (visible only in flight) was bright orange. It nearly always has its wings folded when it lands, though, so the only images I have are of the yellow undersides:

The brown patches on the wings indicate that this is a female. A good clue to its being an orange and not another kind of yellow or sulphur is that there are only two orange butterflies in this butterfly family: tailed orange and sleepy orange. As long as you see the orange wings in flight, you’ve got a 50-50 chance of identifying it right away. And the tailed orange has a very different wing shape, so… About as easy an ID as they come.

Here’s the other side of this beautiful butterfly:

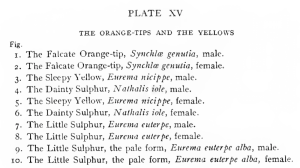

The “sleepy” in the name comes from the marking that looks like a “closed eye” in the forewing. Very few internet commentators give an illustration of this, at least those who work from live insects, because it’s very difficult to get a good photo of this butterfly with its wings open. But if you do manage it (and I haven’t), or you just use specimen photos, you can see the two spots that do indeed suggest closed eyes, at least to those with a little imagination:

And apparently John Henry Comstock, the godfather of entomology in America, gave this species the first part of its common name based on that character.1 I’m not sure when the common name changed from Comstock’s original Sleepy Yellow to the current Sleepy Orange, but it helps easily distinguish it from the other Eurema species: if you see orange, you know it’s not one of the “yellow” yellows. Here’s the picture of it from Comstock’s How to Know the Butterflies:

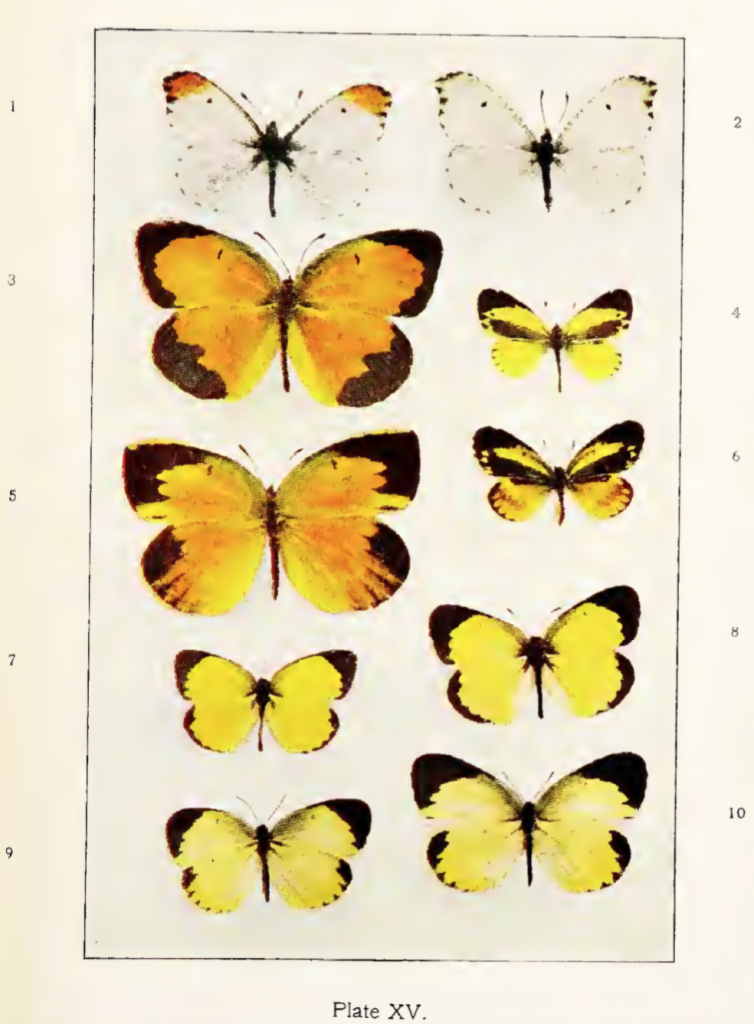

It’s surprising how many different guides don’t show winter and summer forms when they’re different, or female and male; for Sleepy Orange, there’s quite a difference, so you’d need to show all four forms to really help your reader. The yellow on the summer form is “clean,” with the various black markings showing up in stark contrast to the brilliance of the ground color. Minno and Minno (1999) illustrate this species (and most other species) quite well, with two male and two female specimens, one for each form (click the picture if you’d like to see the caption at legible size):

Like several of the oranges and sulphurs, Sleepy Oranges enjoy both the flowers and the leaves of many kinds of cassias; mine is Senna mexicana, var. chapmanii, native to Florida and the West Indies. When it blooms (when the caterpillars leave it alone long enough for it to do so!), it has a pretty yellow flower. I saw one the other day, but it was so windy I wasn’t able to get a picture of it. Here’s one from April instead:

Enjoy!

References

Cech, R. and G. Tudor. 2005. Butterflies of the East Coast: an observing guide. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Comstock, J. and Comstock, A. 1904. How to Know the Butterflies. New York: Appleton.

Minno, M. and Minno, M. 1999. Florida Butterfly Gardening: A complete guide to attracting, identifying, and enjoying butterflies of the lower South. Gainesville: U of Florida P.