If you’re a native plant gardener, it’s easy to let your focus on native plants and animals blind you to the characteristics of non-native species. But one of the most important non-native species worldwide is the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Because they’re so common, I frequently opt not to take pictures of them, preferring instead the more unusual “sweat bees” (halictids), with their bright green bodies and unpredictable (to me at least) sighting opportunities. This gal, for instance, was rescued from drowning in my backyard pool; she’s still in the net (she recovered and flew away):

But honey bees are in my yard each and every day, from the first glimmer of gray in the early morning to the last fading bit of the gloaming after sunset. And they’re pretty amazing creatures in their own right. They pollinate much of the country’s food supply, which I think is just lovely (I love to eat!). They make honey, which I think is delicious (I love to eat!). And they pollinate the clover in the cow paddies of the Midwest that some few lucky cows that aren’t part of the industrial feedlot supply get to munch on. (Did I mention that I love to eat?)

I knew that bees were declining, due, it is suspected, to use (mis- or over-, I’m not sure) of neonicotinoid pesticides to control harmful insects on our monoculture food crops. Unfortunately, these systemic insecticides don’t discriminate: they kill the bad (pests) and the good (pollinators) alike!

I also knew that bees work pretty hard (they work my yard much longer than I do, but I try not to feel too bad about it: ‘m just one person; they are a multitude, and that IS their day job).

What I absolutely never knew about honey bees, though, is that they have hairy eyes:

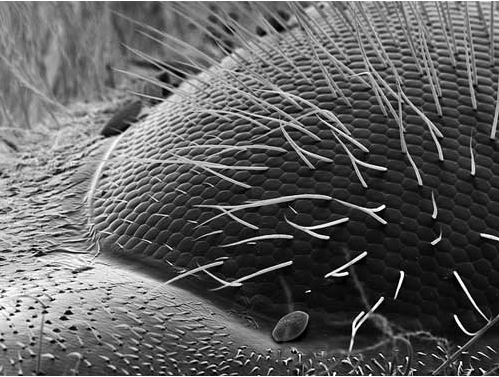

In the picture above you can see the hairs that arise from the spots where the facets of the compound eye meet. It’s a bit unclear to me whether these come from EVERY intersection or just some of them; the micro photos I’ve seen are split on the issue. In this amazing scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of a honeybee’s eye, there are hairs at what look like random intersections of ommatidia (the individual facets that make up the compound eye):

In that shot, which appeared in Rose-Lynn Fisher’s 2010 Bee, you can clearly see that not every facet junction has a hair growing out of it.

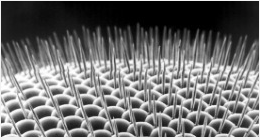

But in this random shot from the interwebs (source citation needed), which admittedly doesn’t show all the junctions as clearly, it looks like there’s a lot more hair:

So which is it? According to the beekeeper and blogger whose site I first saw the above image on, “These hairs are believed to detect wind direction and allow the bees to stay on course in windy conditions. When these hairs were removed from bees in a 1965 experiment, the bees could no longer find their feeding sites.” I’ll have to source that study.

I don’t really know the answer, but I love to have a new question to track down. And that’s one of the great things about turning your (and your camera’s) eye to the simple things: you can always find new questions!

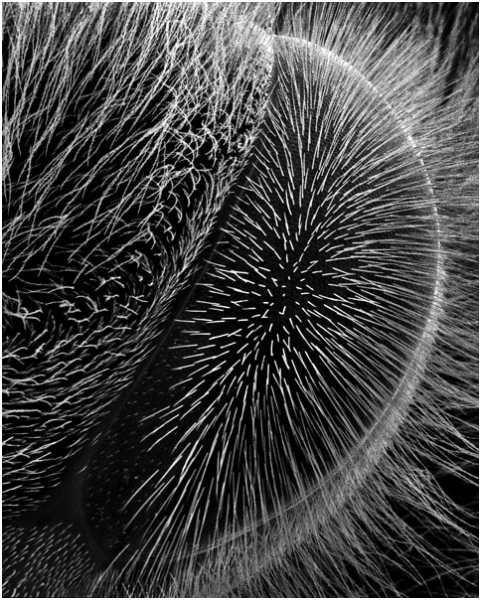

I suspect that the relative abundance of hairs at ommatidial intersections is largely a question of the area of the eye in question and the angle from which the photograph is taken. Here’s another shot by Rose-Lynn Fisher, again from that incredible book about bees; it seems to show many more hairs than the first image, but near the margins of the eye, there are fewer hairs (makes sense, since they would crowd up against the hairs on the head if they grew thickly all the way to the edge:

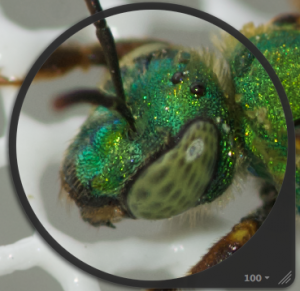

I do know that, unlike the honeybee, most bees (and their cousins, the wasps and ants) do NOT have hair growing out of their eyes. Here’s a sweat bee from my yard:

And here’s a close-up of the eye from that image, where you can clearly see the lack of hair in the compound eye:

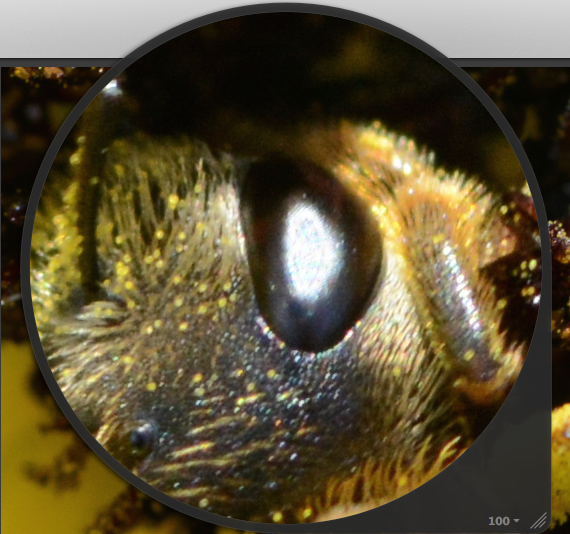

And, because she has such pretty eyes, here’s a close-up of Agapostemon splendens, the first bee in this post:

So, what do you think? Do the eyes have it? (Groan all you want; it’s my blog!)

Honeybees have hair growing from their eyes so that the bee and tell how fast it is flying. The faste3r the bee flies the more deflection there is of the hairs.

Thanks for the comment; I’d love to be able to read more about this idea. Do you have a source for that info? (It certainly sounds plausible!)

I vote my regret to the above comment.

because,if you say, bee decides the speed with which it is flying with the help of this hair movement….it is also possible from the movement of hairs on the other parts also..

no need of hair on eye to determine speed.

Hello! I am writing to request permission to reprint the referenced article to take to presentations I give to elementary school children (and others) as a reference for factual information about Honey Bees. I don’t charge anything for these presentations, in fact, spend a bit of my own money as a hobbyist/educator to stimulate folks of all ages to get more “earth friendly” at all levels, but especially to our pollinators! I will NOT sell or otherwise infringe on your copyrights – I just love having colorful pictures and fun facts to share! Thank you so much in advance for your consideration!

I also give presentations as a volunteer educating about helping our declining pollinators. May I use your photos?

Sure. The uncredited ones on this page are mine. The others are published photos and aren’t really mine to share.