Grasses don’t get a lot of love. People walk on them, dogs do their business on them. If they get noticed at all it’s only for the time it takes the gardener to sigh or curse, depending on temperament, at how tall the grass has gotten before heading off to fire up the lawnmower. Even native gardeners like me often don’t bother to know the various species they might have in their yards, except for the showy ornamentals like muhly grass or purple lovegrass.

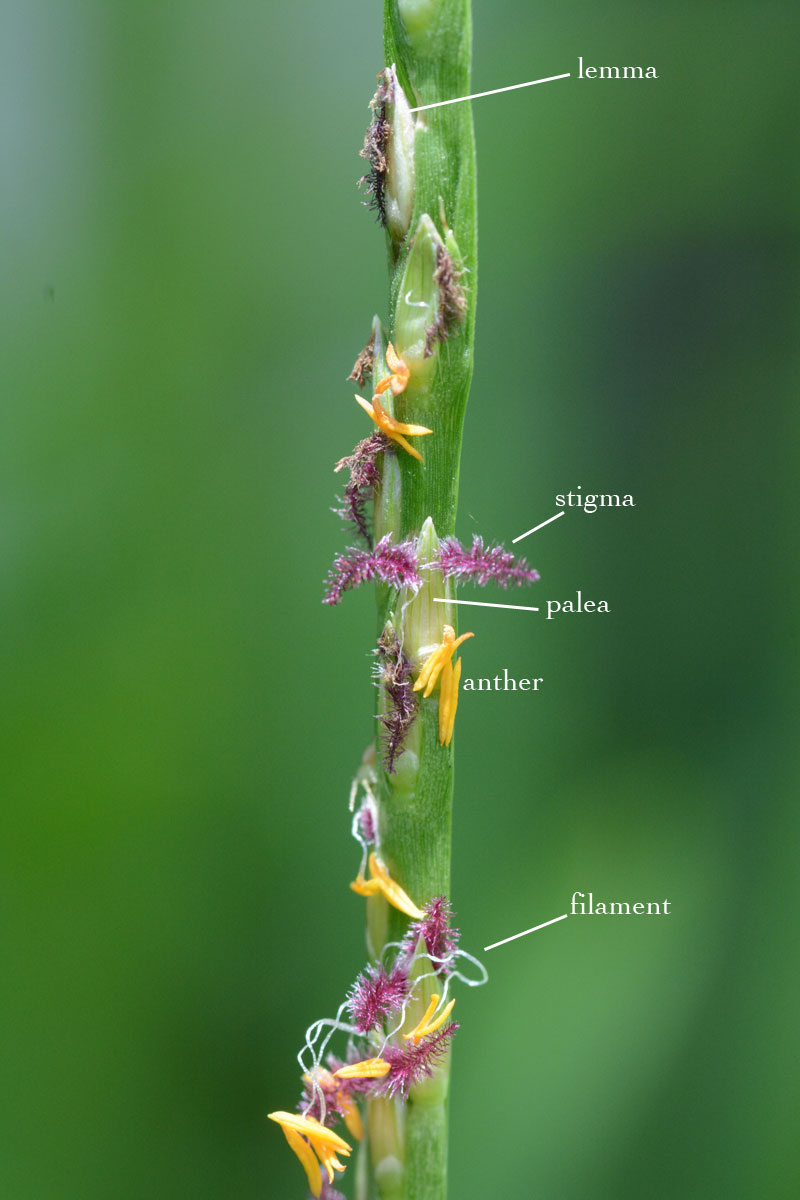

They’re so overlooked that people forget that they truly are angiosperms, flowering plants. I was reminded of this the other day when I was out chasing bugs for the camera and I noticed the exquisite flowers on a spikelet of grass in the back yard.

The species is the ubiquitous St. Augustinegrass, which is supposed to require a lot of care (read, fertilizing, weedkilling, pesticide applications, frequent mowing) if you want to use it as turf here in South Florida, as many homeowners do. My experience was completely different, however: all I had to do to get this grass to invite itself into my yard was mulch the back yard completely and then let it grow in. It came on its own, with no encouragement from me, and has been spreading in competition with two or three other species of grass and a few nongrassy flowering ground covers like Mexican Clover (Richardia grandiflora). But it’s doing quite well, having conquered about half of the nonplanted area in my back yard, and it’s making good inroads into the clover-dominated terrain.

All this while I’ve been doing absolutely nothing that your typical lawn-happy homeowner does. Zip, zero, zilch, nada.

Of course, without all the fertilizer and weedkiller and other chemicals that I refuse to introduce into my local environment (my children play in this yard!), it’s not a beautiful monoculture turf, but that’s not really what I’m looking for in my native-planted back yard. And since I prefer the meadow to the golf course, I’ve let the grass grow up tall around the edges, where it grows the most beautiful little flowers, if you take the time to look closely enough.

See?

Grass Terminology

I still haven’t mastered my graminology, so I have to have my references next to me when I write about it, but according to the dean of Florida botanists, and the first graminologist I’d ever heard of, Walter Kingsley Taylor, the flowering part of the grass you see pictured above is usually called the culm, and depending on species may be “single (simple) or branched (multiple)…creeping, ascending, spreading, erect, abruptly bent (geniculate), or prostrate (decumbent).” For this species, they are “branching, creeping, compressed, terminal and axillary.” (I think the comma after “compressed” is a typo.)

From just looking at the picture above, I can tell you in my own words (and then in translation to graminological terms) that I love the purple spikelets (stigmas), the gold whatzits (technically called anthers, familiar to those who know wildflowers), and the little white trailing whoozits (filaments). They sure are purty, ain’t they?

Many grasses propagate vegetatively. That means they spread by growing sideways, rather than needing to grow from seed. They spread vegetatively by two means: stolons, or aboveground runners, and rhizomes, or belowground runners. St. Augustinegrass sends out long aboveground runners, so it uses stolons.

Etymology

This genus’ name is derived fro the Greek words stenos, narrow, and taphros, trench. Again according to Taylor, this refers to the shallow cavities or depressions of the rachis. What’s a rachis? Well, according to our local graminologist, George Rogers up at Palm Beach State College (Palm Beach Gardens campus), this is:

The species name is Latin and has been adopted by botanists into the English word secund (not a typo): a botanical term used of plants when similar parts are directed to one side only, as flowers on an axis. (Lat. secundus, “following”). It’s not entirely obvious from my shot of the flowering St. Augustinegrass, but the flowers truly are on only one side of the “stem.” I had a hard time finding one of these in flower in the right light; most of them were on the shady side of the stem.

References

Bradford, J, G. Rogers, and J. Wilkinson. Grasses of Palm Beach and Martin Counties. floridagrasses.org.

Taylor, W. K. (2009). A Guide to Florida Grasses. Gainesville: U of Florida P.

Dear Ben, I love grasses and I loved your photo of the Stenotaphrum spike!

Could you please tell me how have yo taken it?

I teach botany in Uruguay and I never could take a picture like yours

Sincerely

Ana

Dear Ana,

Glad you liked the photo. I use a 100-mm macro lens on a DSLR. For this image, I used a then-new Nikon D7100. I was less than a foot away, and used natural light instead of a flash, since it happened to be a nice sunny day. Without a macro lens, detailed photos of small subjects are quite difficult. With a macro lens, detailed photos of small subjects are STILL quite difficult; it takes a while to discover a technique that works for you. I rarely use a tripod, so I consider it a minor miracle when any of my shots comes out in focus.

Thanks for this image! Our mowed St Augustine lawn in Mississippi doesn’t get a chance to flower, but we have started a Wilderness area that has been unmowed for three years. Just saw these beautiful flowers there, but I could never take a photo like this. So glad to know what it is.

Thank you for your humorous and educational post! Oddly, we have had an excessive amount of rain in June and July this year at my north Texas residence and we haven’t been able to mow regularly. I noticed our St Augustine was blooming as a result and was quite astonished to see this. As you mention, and your photos depict, the blooms are quite intricate and colorful. Thanks for sharing!

Fantastic description