The problem: 6 peeling, light-polluting fixtures grace the exterior of the secretary of the Palm Beach County chapter of the International Dark-Sky Association, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the reduction of light pollution and skyglow.

The solution: a trip to the local Lowe’s home center and a little “sweat equity” as they say on those TV shows.

Read on to see how it happened!

I’ve lived in Florida for over a dozen years now, and have enjoyed its abundant opportunities to get out into nature day or night. During the day, I enjoy birding any of the many natural areas in Palm Beach County (most, if not all, administered cooperatively by the local municipality and Palm Beach County’s department of Environmental Resources Management). At night, I like to turn my telescopes to the stars and planets to take advantage of the warm, humid climate, which can provide good views of celestial objects.

I’ve known for years, though, that the stars are better out in the country than they are in the city. Those “billions and billions” of stars that we all know about are reduced to “dozens and dozens” in most urban areas. But get out into the desert, away from the light-polluted city nights, and you will be astonished at just how many stars there really are up there. On any given night, a good dark-sky site can show you upwards of 2,000 stars visible to the naked eye. Not quite billions and billions, but surely an improvement on the dozens visible from my backyard. (The theoretical number of naked-eye stars is around 6,000, but of those, half are on the wrong side of the horizon to see, and about one-third of the remaining total will be obscured by your local horizon.)

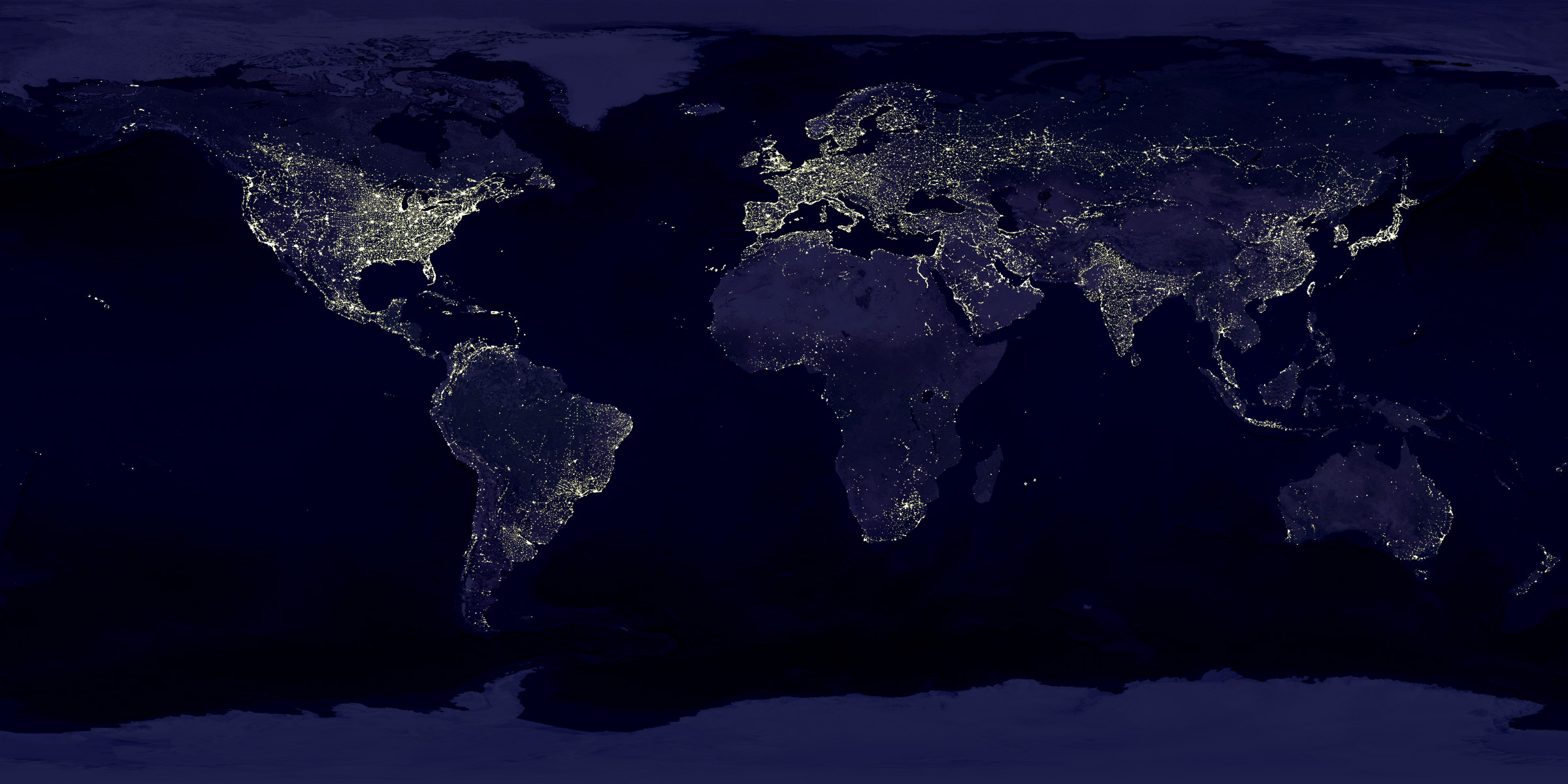

All of this assumes, though, that you have access to a decent dark-sky site. And lately, that has become a rarer and rarer thing. It’s estimated that nearly 75% of children born today will never see the Milky Way, because of the light pollution in their urban night sky:

The view here in south Florida is just as “beautiful,” but that beauty is visible only from an astronaut’s perspective:

From our terrestrial viewpoint, it looks more like this scene from our local observatory at FAU:

Last year, a few people here in Palm Beach County decided to try to do something about this problem. We founded a local Palm Beach County chapter of the International Dark-Sky Association (Find us on Facebook; visit our website), of which I am the secretary. So I decided to do what “they” have been saying for years: think global, act local. I took a quick inventory of the light-polluting outdoor fixtures at my house. And oh my goodness! I had six of them!

1. This light was our front “porch” light; note how it shines up and sideways at least as efficiently as it illuminates the ground.

2 and 3. The other two lights in the front were twins to this one, only larger and with an array of special bulbs. The bulbs were burned out when we moved in and I never replaced them, knowing that I would only be replacing the fixture as soon as I could. Here is what they looked like during the day (no night-time view for these, as they never functioned):

You can see that these fixtures needed replacing not just because they would have been abysmal light polluters if switched on after dark, but for their daytime looks as well. While they might have been handsome when new, the harsh sun here has baked the finish right off them and made them rather dilapidated.

4, 5, and 6. We had a similar situation in the back yard: two twinned light-polluting fixtures by the French doors and a “dock light” by the garage entry, all with peeling finish.

Here in the after-dark shots you can see the “decorative” light in the foreground and the “functional” light by the garage entry door in the background throwing light in all directions, up, down, and sideways:

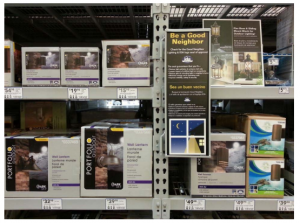

All of these needed to be replaced. So, since I had a job of work to do, and I wanted to keep the budget under control, I decided to see if I could do it myself. I’ve changed light fixtures before; how hard can this be? Short answer: not too hard. I went to my local Lowe’s, where they had a display like this (this one is from Boynton Beach, but the displays are in every Lowe’s):

I purchased two different types of fixtures, in two sizes each: two medium and one small “Ellicott” model for the back yard, and two medium and one small of the dressier “Dovray” models for the front yard. While all of these fixtures are full “cutoff” models, they are not fully focused, so while no light goes up, there is a bit of horizontal light that could be better directed downward through the use of internal baffles or reflectors. But those additional elements raise the cost of each fixture substantially, and this upgrade was already nearly $200. (Yes, that’s right: not even $200 for 6 brand new full cutoff light fixtures. This is not an IDA discount; anyone can go pick these things up for that amount.)

Here they are:

It took about half an hour to remove each old fixture, strip the wires down to new copper, hook up the new fixture, mount, seal, and repaint the wall. One or two fixtures took a bit more effort (the original installation hadn’t been sealed on one of them, and water had been coming in for over a decade, so I had difficulty unscrewing the old mounting hardware; I actually had to pay an electrician $50 to come out and help me), but by and large it was a simple, repetitive exercise and I’m more than pleased with the results.

In fact, even the problem posed by the rusted fixture had a beneficial side-effect: I was able to discover the source of that persistent water leak downstairs! Here it is; note the rust indicating prolonged exposure to water through the unsealed and poorly mounted fixture:

After the project, I had brand new non-light-polluting fixtures that are attractive day and night. Here’s the front, daylight view (apologies for the somewhat Cubist perspective) of the new fixtures:

And here’s the same scene at night.

And here’s the view in the backyard, with two of the three new fixtures visible:

While the light still “leaks out” a bit horizontally, the uplight has been completely eliminated, which was the goal of the project. Not bad for a few hours’ work and a project that, without the shoddy workmanship of the original installation (which has nothing to do with the light pollution abatement), would have come in under $200!

It may not solve the global problem, but it sure helps the local area.