Everyone’s heard of flash mobs by now—you know, those social media–inspired and -coordinated events where a group of smartphone-wielding people with too much time on their hands descend on an unsuspecting locale and do something silly/creative/fun/tragic?

Well, birds have been doing mob scenes since long before our hominid ancestors descended from the trees. And photographers have had flash bulbs since long before Facebook and Twitter erupted onto our social scene. (Come to think of it, birds have been tweeting since, well, you see where I’m going with this…) Combine the two, and you get a mob scene—Screech-owl style!

When you work from home, you always have to keep your ears peeled for unusual things. A persistent cheep from a cardinal, some angry twittering from a palm warbler, even some darting from a hummingbird or two—to the photographer who knows a thing or two about birds, this can only mean one thing—a mob scene!

See, songbirds are a pretty wimpy lot. They don’t have strong talons to grapple or fight:

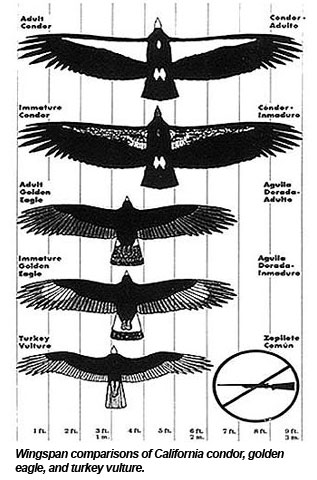

They don’t have enormous wingspans to soar above it all:

- Image from http://birdsflight.com/bird-largest-wingspan-world/

They don’t have the silent wingbeats of the owl, or its enormous, night-adapted eyes.

So they wind up in a lot of other birds’ bellies. Their only defenses are their eyes and their wings. They need to see and avoid the predator before it sees them.

On the other hand, most avian predators run on a tight energy budget. They’re not feeding on abundant seeds or insects. Their prey is fast and, well, they can fly away at a moments’ notice. If that happens too many times, your sharp-taloned, long-winged, silent-hunting apex predator starves, which is, frankly, rather embarrassing.

So your hawks and your owls have to be pretty cagey about things. They vastly prefer to sneak up on an unsuspecting victim, break its neck or otherwise dispatch it, and repair to a convenient roost to pluck and eat their prey.

Over time, songbirds have adapted to the sneaky strategies of their predators by forming temporary flocks, known to birders as “mobs.” It seems that the more eyes there are watching, the less likely any individual bird is to be snuck up on and removed from the gene pool. But despite the old saw that “birds of a feather flock together,” these mobs are rarely single-species flocks. Instead, representatives from most of the species in a given area flock seem to flock to mob a predator.

And that’s what called me out from my office this afternoon—some insistent cheeping from our neighborhood cardinals in the shrubs between our house and our backyard neighbors. Along with the cardinals, there were see some common birds (Palm Warbler, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher) along with others that I don’t often see in the back yard: Painted Bunting—alas, no pic—and this Ruby-throated Hummingbird:

Here’s the Palm Warbler, too:

All of these birds were alerting each other to the presence of that most cryptic of predators, the Eastern Screech-Owl:

This was a most unusual bird; I was able to get to within about 3 feet of him without him leaving. And he stayed out there long enough for me to head inside, grab my other lens, and come back out. He did turn and look at me over his other shoulder, though:

I don’t know if this is the same owl that we hear from time to time when we’re out in the back yard, but I do know that he probably wasn’t successful in any hunts this afternoon, thanks to the avian flash mob.

Cheers!