The Monday after Thanksgiving is a great time to get out to a nearby natural area. While most folks are back at work after a four-day weekend, those of us who have the foresight to request this day off get to experience something fairly rare around this time of year: solitude! The prospect of some alone time, combined with the knowledge that two of Palm Beach County’s best birders had reported a juvenile Red-headed Woodpecker at a location near me decided my destination on this fifth day of a four-day weekend: Pondhawk Natural Area, which, as loyal readers of this blog know, was formally opened just a couple of months ago.

And on this day, as expected, I had the place all to myself!

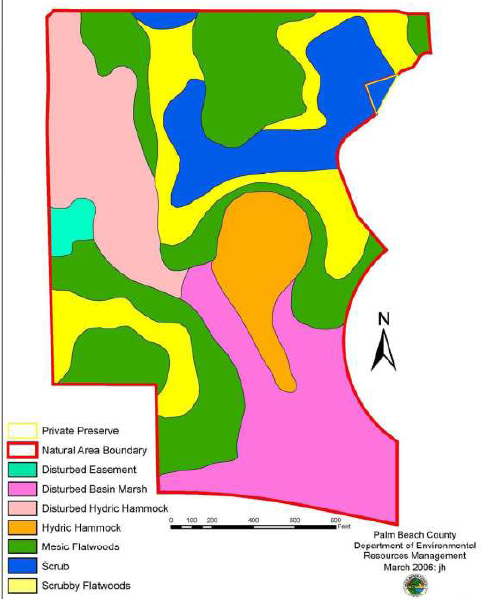

I started out on the concrete walking trail, chasing warblers and other birds as the fancy struck me, and I wound up assembling a fairly respectable list without even trying very hard—28 species, including House Wren, American Kestrel, Osprey, Red-shouldered Hawk, and the target bird: Red-headed Woodpecker. But that wasn’t the only, or even the primary, goal of the excursion. I just needed to get back out into one of the prettiest natural areas in Boca Raton. It’s a very pretty park, with 5 different ecological communities (you can’t really call these tiny snippets of area “ecosystems”)—scrub, scrubby flatwoods, mesic flatwoods, hydric hammock, and sawgrass slough.

I spent most of my time on that concrete trail, which winds through the mesic and scubby flatwoods (yellow and green areas in the map below) that surround the pond (the orange hydric hammock in the map), but I also took an excursion onto the sandy trail that leads through the southwestern portion of the site (also mesic and scrubby flatwoods). I never did get onto the trail through the scrub proper.

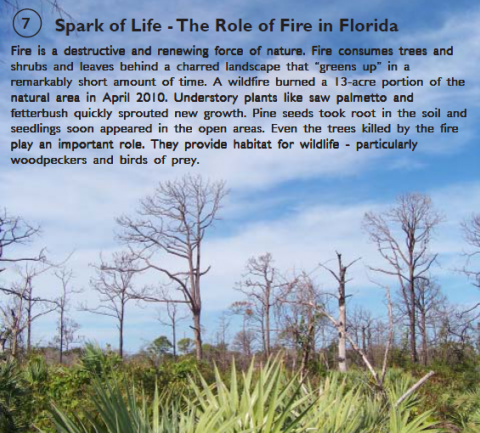

Both scrubby flatwoods and “true” scrub are dominated by shrubby, scrubby plants that don’t need a whole lot of water: sand live oak, saw palmetto, prickly pear cactus, etc. Where there are “woods” around (hence scrubby flatwoods), they are usually sand pine or, in slightly wetter scrubs (mesic, halfway between dry [xeric] and wet [hydric] sites), slash pine. The flatwoods areas at Pondhawk have numerous snags (dead trees left standing in the wake of a wildfire on this part of the site back in 2010) and living slash pine trees, providing excellent foraging and even nesting habitat for woodpeckers like the red-bellied (common in Palm Beach County) and red-headed (much rarer in Palm Beach County):

Another characteristic plant of scrub or scrubby flatwoods is Feay’s Palafox, with its interesting tubular flowers arranged into a very pretty cluster (called an inflorescence):

You should always look closely at flowers; then, when you think you’ve seen everything, take a picture. I knew there was an ant hitchhiker on this flower, but I didn’t notice the pale creature on the second “tube” from right until I got the image onto the computer.

I have no idea what the pale creature is; I was assuming jumping spider at first, but it’s not in focus and no matter how hard I squint, I can only make out 4 or 5, not 8, legs. And the body is rather elongate for a spider, although some of those tiny jumping spiders can be fairly “tubular.” Heck, it might not even be an animal!

When I arrived at Pondhawk, I was just hoping to see some pretty scenery like that flower; I had little to no expectation of actually encountering the “object” of my visit (the aforementioned Red-headed Woodpecker). I don’t chase birds, and I don’t really even go out of my way for them; I just like to get out into nature and, while I’m there, they’re one of the more interesting things to look at—when I can tear myself away from the plants and the insects, that is. And when I do set out with a specific bird in mind, more often than not I miss it, anyway, so perhaps I’m only making a virtue out of necessity by deciding to focus on the whole experience, rather than the “goal.”

This time, though, I got a bit lucky: I actually did “get” the bird. I can’t say, though, that I got a satisfying picture of it; it was always just too far away, or just on the wrong side of the sun, or the sun was behind a cloud, or it flew right over my head and I couldn’t focus fast enough. Still, I managed to document the bird, which was nice:

Everyone’s still a bit confused about what this bird is doing here, so far south of its known nesting sites in the county. Red-headeds are slightly migratory, in that they move locally in winter to exploit better resources than they can find near their nesting sites, but only if their nesting sites are deficient in some food resource. Up north, a poor mast crop (acorns) is what triggers this migratory response; down here, with seemingly abundant year-round resources, it’s a bit of a mystery why this juvenile bird would wander like this.

Eventually the woodpecker got tired of me chasing it from snag to snag, and decided to fly right over my head (too quickly for me to get a picture, drat it) and back up to a site far enough away that it wasn’t worth hiking over to, so I continued on my way and left him (or her) in peace.

On the way out I got a couple of other decent shots, like this Red-shouldered Hawk perched on a tree overlooking the pond, thus doing its best to look like the avian version of the “pondhawk” for which the site is named:

What really got me excited, though, was my first-ever sighting (well, documented with a photo anyway) of one of the spreadwing damselflies, Carolina Spreadwing (Lestes vidua):

Carolina Spreadwing is the only spreadwing we’re likely to see this far south in Florida; the only other species that occur in our area are either blue or green, not mostly brown. Very little appears to be written about this species, so I can’t tell you much about it. The generic name, Lestes, means robber (some say predator) in Greek; vidua means widow in Latin. The official etymologists of North American odonates, Paulson and Dunkle, list this specific name as “widow; allusion unknown.” And that’s all I can tell you about it as well! This very young female (based on coloration) did her best to elude me, and she even exhibited some behavior that our great Florida odonatologist, Sid Dunkle, describes as follows:

Interestingly, they close their wings over their backs, and drop their bodies to parallel their perch, when a dragonfly flies near. Pairs in tandem do this also, but the approach of a human does not elicit this behavior.

Now, there were plenty of dragonflies flitting about, so I can’t exclude the possibility of this damselfly doing this in response to them rather than to me, but on both perches that I chased this little lady to, she closed her wings over her back in what I thought was a response to my approach:

This behavior confused me so much that I couldn’t be positive this wasn’t a “normal” damselfly that was exhibiting spread-wing behavior, rather than a spreadwing exhibiting “normal” behavior. When I got home and read Dunkle’s description, I felt a little better about my ID on the bug. It still hasn’t been confirmed by either bugguide or Odonata Central, but I’m fairly confident she is who I say she is.

Hope to see you out and about next time!