It’s millipede season again here in Boca, although down in the Keys, it started back in August. Don’t worry, though; they’re no threat to your health or safety. From the UF/IFAS factsheet ENY-221/IG093 (available on their website):

Centipedes and millipedes are commonly seen in yards and occasionally enter homes. Neither centipedes nor millipedes damage furnishings, homes, or food. Their only importance is that of annoying or frightening individuals.

That may be true, but they are certainly good at annoying me this time of year. And this year in particular we seem to be experiencing a bumper crop of them. Here’s a closeup of a particularly striking one that Eric pointed out to me the other day:

Whenever the kids see one, the reaction is pretty intense:

First, some taxonomy: centipedes and millipedes are not insects. Both belong to taxonomic groups named after their most prominent features: their many, many legs. Centipedes have one pair of legs per body segment and belong to the class Chilopoda (from the Greek chilios, “thousand”); millipedes have two pairs of legs per body segment and belong to the class Diplopoda (from the Greek diplo, twofold). Both taxonomic classes are subsumed into the subphyllum Myriapoda. Thus, they can be called chilopods, diplopods, or myriapods with equal accuracy (but not equal specificity). However, if you clicked the “taxonomy” link above, you’d have discovered that nobody really knows what they’re talking about, taxonomically, with regard to the millipede.

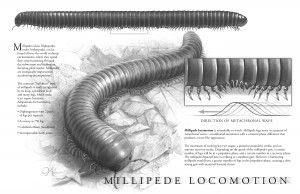

Next, some anatomy. Millipedes (centipedes too) consist of two basic regions: a head and a trunk. The trunk is made up of a series of body segments bearing legs (remember, one pair of legs = centipede, two pairs = millipede) on all but the first four thoracic body segments. As a very convenient website puts it.

Most of the trunk segments carry two pairs of legs (hence the name ‘diplo’- two ‘poda’ – feet). This is because the apparent trunk ringed segments are actually ‘diplosegments’ formed by the fusion of two trunk segments. The first ring after the head (collum) is legless and the following three rings carry one leg pair each.

This fusion of body segments in millipedes explains why their cousins the centipedes are much more flexible, capable of winding around and over objects and bending in more than one segment at a time, while millipedes proceed more, as Thomas Eisner writes, “bulldozer fashion.” This is because the body segments of millipedes are actually fused together, rather than individual articulating segments. So while a millipede can curl up, it can’t really bend in too many directions at once.

If you’d like to read more about their fascinating method of locomotion, click on the image below (by Julia Molnar, PhD student at the Royal Veterinary College and paleoartist extraordinaire).

Myriapods are detritivores, which means that they feed on decaying plant material and organic matter; they don’t damage living plants. They also don’t bite. They do emit chemical secretions that could, possibly, bother someone, but in quantities so small that it’s rarely a problem unless a curious researcher (usually a child) gets too close to the wrong species.

While there are many species native to Florida, there are also many introduced species. The two species most commonly seen at our house are the native Chicobolus spinigerus, the Florida Ivory Millipede, and (I’m fairly sure; millipede ID is not my specialty) the introduced Trigoniulus corallinus, Rusty Millipede.

Here’s one that Daniel and Eric enjoyed pointing out to me:

I believe it to be the Rusty Millipede, but the only resource I know of that even lists all the Florida species (Shelley 2000) does not include photos. There are only 51 species according to this source, though, so it wouldn’t be outrageously hard to try a Google image search for each one; it’s just time-consuming. There might be a native look-alike, for all I know. There’s another introduced species, Rhinotus purpureus, that looks quite a bit like T. corallinus; far too similar for a nonspecialist like me to tell, at least without a key.

Chemistry

The chemical defenses of several Florida millipedes have been studied by the late Thomas Eisner, who used to visit the Florida scrub up at Archbold Biological Station on research summers when he wasn’t teaching at Cornell. One species, Floridobolus penneri, the Florida Scrub Millipede (and endemic to that habitat), emits a mixture of benzoquinones that completely deters all insect predators, except for the larvae of one beetle, specially adapted to prey on these millipedes. These larvae have their own chemical offense (the gut fluid) that preempts the millipedes’ defense by paralyzing the millipede completely, so that the defensive glands of the millipede never get a chance to come into play. You can read all about it here., although I read about it first in Eisner’s book for the layperson, Secret Weapons.

In fact, monkeys and grackles appear to use the secretion of one Caribbean species now found in Florida (the yellow-banded millipede, Anadenobolus monilicornis) for its insect-repellant qualities. At least, both primates and birds have been documented rubbing this “bug” on their bodies or under their wings. Here’s one of the many that frequent our outside walls and, sadly, our inside ones as well (They dry up pretty quickly indoors, so it’s best to just leave them alone and then sweep up the detritus):

I’ve seen a similar millipede referred to on bugguide.net as “Eurhinocricus,” so perhaps there are two species, or there is taxonomic confusion/”updation” at work.

Etymology/Usage Note

Many scientific articles “misspell” millipedes as millipeds. That’s not a misspelling; that’s just the way scientists like to refer to things. Presumably the practice arose from the much more common practice of “inventing” a quasivernacular name from the Latin name for an animal. For example, members of the gull family, Laridae, are often referred to as larids; the Bromeliacaea are often called bromeliads. Thus, I imagine, from “millipede” we get “milliped.”

For example, the most recent annotated checklist of Florida’s millipedes (sans images, sadly), follows this practice:

The milliped fauna of Florida consists of 8 orders, 18 families, 34 genera, and 51 species and subspecies; it comprises six elements: widespread species occurring widely in Florida, northern species reaching their southern limits in north Florida, neotropical species occurring naturally in Florida or adventive there, oriental adventives, Florida endemics, and southeastern endemics.

As you can see, the analogy is imperfect: the quasivernacular name (if that’s what it is) milliped is just a shortening of the already vernacular name, rather than the presumably unwieldy latinate name for millipede (which, you recall, is Diplopoda). If authors called them “diplopods,” I’d understand. I’m still flummoxed by “milliped,” but I’ve seen it often enough to know that it’s not a “mistake.”

Another possibility is that milliped is just the adjectival form of the noun millipede. That is, when describing the attributes of millipedes, one simply drops the final e: milliped fauna. I’m not convinced. After all, the “aberrant” form milliped is used both as noun and adjective.

When you run out of reasoned argument, try the dictionaries.

First, the standard dictionary in American book publishing: Merriam-Webster’s 1th Collegiate. MW11 lists the “normal” spelling, millipede, no variant spellings, a reasonable definition, and gives a date of 1601 for the first usage in its records.

The next resource in my method is the American Heritage Dictionary, now in its 5th edition. It lists “millipede, also millepede,” gives no date, and defines the animal more or less straightforwardly.

Next, the entomologist’s favorite dictionary, no longer in print but available online: the Century Dictionary, which is often very helpful in providing meanings for taxonomic names. That resource lists millipede as “same as milleped,” and under that entry (milleped, milliped) defines the animal more or less straightforwardly.

Not much help explaining the variations in spelling, unfortunately.

Time to bring out the really big guns: the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) lists milliped as a variant of millepede. Under that main entry, the OED lists even more variants, some less and some more familiar: millipeed, millepide, milleped, and, last and apparently least, our version, millipede.

So the “new” spelling is the one we Americans are used to: millipede. The OED, lovely resource, dates the 1601 spelling as “millipeed” (from a translation of Pliny), a 1706 millepeda, and gives two resources (1835 [Kirby] and 1877 [Huxley]) for the modern American spelling, millipede.

Conclusion? Usage is mixed. Go with whatever your journal editor recommends, if you’re publishing. Go with whatever pleases you, if you’re blogging.

References

Eisner, T. 2005. Secret Weapons. Defenses of Insects, Spiders, Scorpions, and Other Many-Legged Creatures. Cambridge, MA: Belknap (Harvard UP).

Shelley, R. M. 2000. Annotated checklist of the millipeds of Florida (Arthropoda: Diplopoda). Insecta Mundi.Paper 316.htp://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/316

We live in Vero Beach and this is the first year we’ve seen an enormous increase of them. Is there a season – i.e. will they be around a month from now?

They tend to be seen the most during the humid months; as the humidity drops, they tend to burrow deeper into the leaf litter and soil. So I would expect, although I don’t know for sure, that you won’t see them as much in December.

What do you use to stop them?

Stop them from doing what? As long as they’re outside in my mulch, I have no problem with them. Inside, if I spot them before the cats do, I try to sweep ’em up and put ’em outside. I don’t have any warm and tender feeling toward them, but they’re not on my do-not-tolerate list.