A bird that’s probably familiar to many of you is Chaetura pelagica (Linnaeus, 1758), more commonly known as Chimney Swift. It’s been described by Alexander Sprunt (1954) as “resembl[ing] in appearance a cigar on wings” because of its tubular body and long, long wings. Most of the time you see it on the wing, flying overhead chasing down its insect prey, and twittering like mad. It always reminds me of the last line of one of the most famous of Keats’s odes, “To Autumn”:

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,—

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

Keats’s swallows are what we call here in the States “Barn Swallows,” Hirundo rustica (Linnaeus, 1758). They are the most widespread species of swallow in the world, and they are what the poet saw at dusk on September 19, 1819, as he wrote what was to become the most anthologized poem in the English language. We have Barn Swallows here in Florida, with records in every season for Palm Beach County. We see them gathering in large flocks on our annual trips to the flooded fields of western Palm Beach County in August, and they are even reported breeding in neighboring Hendry County.

But the bird that occurred today at my house, while it looks largely similar to the swallow through the process known as convergent evolution, is not even closely related to the swallow family. (The idea of convergent evolution is that animals that specialize in similar ecological niches, the way swallows and swifts specialize in catching insect prey on the wing, often evolve similar body shapes. In this case, long, pointed wings and a beak with a large gape. In a more general example, the wing itself evolved separately in the mammalian, insect, and avian groups.)

Chimney Swifts are actually more closely related to the hummingbirds than to the swallows they resemble. This fact has been known at least since Arthur Cleveland Bent’s magisterial series on North American birdlife: Life Histories of…. Bent published the volume on Cuckoos, Goatsuckers, Hummingbirds and their Allies back in 1940 as United States Museum Bulletin 176, although most birders with extensive libraries have the Dover edition, which the publisher released in two slim volumes to increase their profit margins. (After starting this post, I found out that the text is available online as well, so you don’t even have to go to the trouble of devoting 3 or 4 feet of bookshelf to the printed version.)

Bent writes of the migratory nature of this bird:

From its unknown winter quarters, somewhere in Central America or on the South American Continent, the chimney swift comes northward in spring and spreads out over a wide area, which includes a large part of the United States and southern Canada.

Individually, the swift is an obscure little bird, with a stumpy, dull-colored body, short bristly tail, and stiff, sharp wings, but it is such a common bird over the greater part of its breeding range and collects in such enormous flocks, notably when it gathers for its autumnal migration, that as a species it is widely known.

Does that last sentence remind anyone else of Keats’s swallows? Hmmm? Well, never mind, then…

The write-up in Sprunt (1954) and Stevenson and Anderson (1994) updates Bent’s “unknown winter quarters” to a locale in the upper Amazon Basin, determined by bird banders in the 1940s, who recovered a few birds banded in Tennessee. According to Sprunt,

The Chimney “Swallow” as it is often and erroneously called, is one of the most familiar birds of the country, as it appears in multitudes about human habitation…. Not the least interesting thing about this very interesting bird was, until recently, the mystery of its winter home. No one knew for certain where it was. Then, in May of 1944, word was received from the American embassy in Lima, Peru, that some bands had been turned in, “secured from some swallows killed by Indians” along the border of Peru and Colombia, some 6 months earlier. Most of the “swallows” were Chimney Swifts and had been banded in Tennessee (F. C. Lincoln, Auk, 61:604, 1944). Thus a mystery was solved and the supposition that some of the birds wintered in South America vindicated.

Bent describes the behavior of this bird in terms of its “curious” relationship to people:

Although the species spends the summer scattered over a large part of the North American Continent, it never, except by accident, sets foot upon one inch of this vast land. The birds build their “procreant cradle” in the chimneys of thousands of our homes and crisscross for weeks above our gardens and over the streets of our towns and cities, yet, wholly engrossed in their own activities far overhead, they do not appear to notice man at all. Indeed, it is easy to believe that the swift is no more aware of man during the summer, even when it is a denizen of our largest cities, than when in winter it is soaring over the impenetrable jungles of Central America.

How do we regard this bird that does not know we are on earth? We are glad to have swifts breed in our chimney; we like to see them shooting about over our heads, and we enjoy their bright voices; yet, do we feel such friendship for them as we feel for a chipping sparrow, for example, which builds sociably in the vines of our piazza? The little sparrow may be wary, and may fly away if we come too near, but at least it pays us the compliment of recognizing our existence. The swift, however, is not even a semitrustful neighbor; it is a guest that does not know we are its host. We may almost think of it as a machine for catching insects, a mechanical toy, clicking out its sharp notes.

But let us note this fact. Every ten years or so the swifts do not appear about our house in the spring. Something has gone wrong on their journey northward. Our chimney will be empty this year; there will be no dark bows and arrows dashing back and forth above our roof, no quick pursuits and chattering in the evening. All summer something is lacking because there are no swifts to enliven the season. We realize, now that they are gone, how we should miss their active, cheerful presence, if they never came back again. But we may be sure they will come back–next year perhaps–to visit us again, this most welcome “guest of summer.”

I always enjoy hearing them pass about overhead, when I’m gardening or swimming with the kids in the pool. Whenever I hear them twittering, I point it out to the boys. Eric is starting to get mildly interested in it, at least to the extent of agreeing that birds are “so pretty” and their songs are “so nice.” Daniel, on the other hand, is absolutely ga-ga over birds, at least the prints of birds that we have hanging on our walls.

Speaking of hanging on our walls, I haven’t even gotten around to showing you the impetus for this post! For the past couple of days, I’ve noticed that there is a rather insistent quality to the chittering near our house, and yesterday I heard flapping in our chimney. Could it be? Could our chimney be blessed with a swift family building its nest?

I still don’t know the answer to that question, but a look up top shows that the possibility certainly exists:

And since our fireplace doesn’t have a flue (there’s something in there that blocks the rain and catches the leaf litter that blows in, but there is evidently still a large passage through which animals can squeeze), this morning my office was paid a visit by one of the birds itself.

Imagine my surprise on entering my little office to hear a flapping inside the room! I saw a little black bird up on top of my tall bookshelves and immediately closed the door to make sure the creature didn’t fly into the rest of the house where it might get irretrievably lost or hurt. Then I opened the window, removed the screen, and began trying to herd it out through the opening. Easier said than done.

After a few minutes of trying to get close enough to it with the screen in hand so that I could sort of shoo it out, I gave up on the hands-off approach and decided I’d better just let it settle down somewhere while I took a few pictures and thought things through. No sooner thought than done.

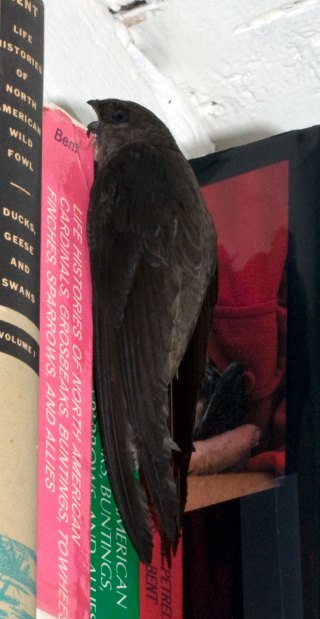

After I stopped chasing it, it seemed to take some comfort, settling in to a cozy resting place on the top shelf, which, as it happened, is the home of my copies of Bent’s fine Life Histories series:

Here you can see it clinging to volumes two and three of Cardinals, Grosbeaks, Buntings, Towhees, Finches, Sparrows, and Allies. (Apparently it can’t read, or doesn’t know its place in the taxonomy of North American bird life!)

Eventually I was able to get close enough to it to take a decent portrait:

Then, perhaps proleptically encouraged by the words I was soon to read in Bent’s write-up of the species (“banders who have handled the birds report that they show little or no fear (or consciousness) of man and appear tame to an extraordinary degree”), I was able to sneak up on it from below and wrap it up in a towel. I was concerned that it would be as nervous and fluttery as it was when I first walked into the room and surprised it, but it went completely still and allowed me to snap a few awkward shots with my left hand, while holding it in my right:

Here you can see the bristly tail feathers Bent described, and you can also see how much longer the wings are than the tail. (“Primary projection,” that is, the difference between the end of the longest of the innermost wing feathers (tertials) and the end of the longest of the flight feathers (primaries), is a different metric, and is of little use in identifying swifts or swallows because they’re always flying so you never see it!)

After a couple of clumsy left-handed shots, I took pity on the poor bird and set it on the windowsill and removed the towel, whereupon it instantly sprang into action, whirred once around the tiny courtyard, and hasn’t been seen since.

References

Bent, A.C. (1940). United States National Museum Bulletin 176. Repr. 1964, New York: Dover. Available online as Life Histories of North American Birds.

Sprunt, A. (1954). Florida Bird Life. New York: Coward-McCann, National Audubon Society, USFWS and Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission.

Stevenson, H.M., and B.H. Anderson. (1994). The Birdlife of Florida. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.