The last few days have seen the finest weather I can recall since moving to Florida. Daytime highs in the low- to mid-70s, overnight lows in the 50s and 60s, a light breeze making sure that even when you’re out in the sun you feel cool and refreshed. This is what living in south Florida is supposed to be like!

When the weather’s this nice, one of my favorite things to do during my lunch break is go out and get dirty. And every now and then, getting dirty involves rolling around in the grass chasing after lovely little damsels. And every now and then, when you chase lovely little damsels you catch them.

Here are some pictures of the lovely little damsels I caught during my lunch break one day this week.

A beautiful, if somewhat immature, female Citrine Forktail (Ischnura hastata):

Doesn’t she have just the loveliest orange color all up and down her body? Were she older, her color would be a bit duller: her abdomen would have blackened up and perhaps become pruinose (powdery/waxy white), her thorax (including her eyes) would have become greenish, and she’d generally look a little less like a bright orange/red sports car.

The next day I saw her, or perhaps her sister or cousin, in the front yard:

Still beautiful, right? This is more likely a sister or cousin, as our original little girl didn’t have any nasty mites on her underbelly, and you can see in the picture above that this little lady has acquired such a hitchhiker. My understanding is that these mites are typically acquired during the damselfly’s larval stage, and they just sort of hang around until they can begin feeding on the adult form.

Next, illustrating the fact that nothing in the world escapes the indignity of being eaten, whether it will or no, two different forktails, a male Citrine and a female Rambur’s are both dining and being dined upon. Reminds me of “Bugs” by Ogden Nash:

Some insects feed on rosebuds,

And others feed on carrion.

Between them they devour the earth.

Bugs are totalitarian.

—Ogden Nash

See the little mites under the thorax of this male Citrine Forktail? They probably bug him a little bit, but from all accounts, unless they are quite numerous they don’t seem to measurably affect his quality of life. April must really be the month for Citrine Forktail here in Boca; my yard has been veritably plagued by them for weeks now (if you can call the presence of beautiful little insectivorous fliers a plague). Just to show how many there were, here are a male and immature female jockeying for space on the same wildflower/weed in my front yard:

And now, toward the end of the month, their larger cousins, Rambur’s (I. ramburii) are showing up as well:

The female in the picture above has captured a nice juicy prey item (looks like a leafhopper) and is happily munching away at it, all the while being happily munched upon in her turn by those leetle tiny mites on the right side of her thorax. (It’s thought that, like the lice on birds, the mites on each species of odonate are separate species. Can you imagine how abundant parasite species must be, if there’s at least one separate species for each host species on the planet? One study of just one type of parasite (gregarines, one-celled protozoans) demonstrated that these organisms tend to be host-specific as well, so when you add up the number of kinds of parasites, then multiply by the number of known species of hosts, you’re dealing with astronomical quantities.)

The female of Rambur’s Forktail is polymorphic, which means that she comes in more than one color form (but only one per customer, please). The individual pictured has what is known as andromorph coloration (from Greek andro-, “male”); that is, her color is almost exactly like that of the male. Her thorax, though, unlike the green thorax of the male, is blue. This color difference means that she is technically immature; if she were older, it would be green just like the male’s.

How can I prove that she’s female? Well, today it was pretty easy: she’s the one on the bottom in the wheel, or heart, position:

Why on earth, you might ask, do these damselflies have to resort to such an odd position for copulation? Well, you see,

Male Odonata are unique among exopterygote insects [ie, those that undergo incomplete metamorphosis, with only egg-larva-adult stages of life, rather than complete metamorphosis, egg-larva-pupa-adult] in having the primary genital orifice and the intromittent organ located at opposite ends of the abdomen. (Corbet 1999)

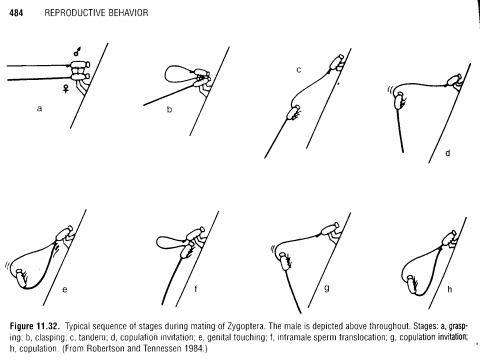

During copulation, the female’s tail tip is pressed up against a secondary genital structure located between the male’s second and third abdominal segments. That structure, called the seminal vesicle, has been packed with sperm from abdominal segment 9, right near his own tail tip—how he manages to first clasp the female and then transfer the sperm would be a complete mystery to me were it not for the helpful illustration from Corbet that I reproduce below—and is being pressed up against the female’s tail tip so the sperm can be transferred from said vesicle to her spermatheca; any eggs that pass through that spermatheca then become fertilized.

Here is a graphic representation of the process from the dean of odonate studies, Philip Corbet (you have to click the image to see all 8 stages; the thumbnail cuts the picture off mercilessly):

The process looks inordinately complicated to our anthropocentric eyes, but it’s worked for odonates, both damsel- and dragonfly, for millions of years longer than primates have been wandering the earth.

And here, just because they came out nicely, are a couple more shots of the beautifully colored male Citrine Forktail:

References

Corbet, P.S. (1999). Dragonflies: Behavior and Ecology of Odonata. Ithaca and NY: Comstock.

Paulson, D. (2011). Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP.