According to Tom Lodge, “the flora and fauna present when Columbus arrived in what he called the New World (the Western Hemisphere) had arrived in the region by their own modes of dispersal, and had succeeded based on their tolerance of the climate, the habitats, competition, and numerous other factors” (183). And that’s why we encourage the use of native plants in your landscape—so the birds that depended on those plants for thousands of years before our houses and driveways and swimming pools and parking lots removed many of them can still have food and shelter as they go about their lives.

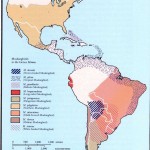

Above, Mimus polyglottos enjoys the shade of, and a snack on, Callicarpa americana. The Northern Mockingbird is one of ten (or so, depending on your taxonomist) species in the genus Mimus, which extends almost from the tip of South America all the way north to Canada, more than 100 degrees of latitude. The members include, roughly from north to south:

- M. polyglottos (Northern Mockingbird)

- M. gundlachii (Bahama Mockingbird)

- M. gilvus (Tropical Mockingbird)

- M. magnirostris (St. Andrew Mockingbird)

- M. saturninus (Chalk-browed Mockingbird)

- M. longicaudatus (Long-tailed Mockingbird)

- M. dorsalis (Brown-backed Mockingbird)

- M. triurus (White-banded Mockingbird)

- M. thenca (Chilean Mockingbird)

- M. patagonicus (Patagonian Mockingbird)

As its common name implies, M. polyglottos is the northernmost representative of the genus. It also has the widest longitudinal range, covering all of North America from east to west (or, since I’m “originally” from California, from west to east!). Back in 1988, when Robin W. Doughty was writing the monograph on them, they were absent from some of the northern reaches of Washington and Idaho; they have since closed that out, according to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s range maps. (See comparison below; click on the images for a larger version)

But Doughty’s text is still spot-on: these birds, where they are found, seem to outnumber all other birds. Describing both abundance and behavior of this species, Doughty quotes Roy Bedicheck: “Bird survey statistics confirm [Bedichek’s] belief that the mockers ‘tyrannize over other bird life by weight of numbers as well as by individual prowess.’ ” (Doughty 19). My sore head from many years ago in California when I got too close to a nest can testify to their tyranny over human life as well as bird life!

Usually, though, they’re quite nice neighbors, with a pleasant voice and plenty to chat about. We get along. Hope you do, too!

References

Doughty, R.W. (1995). The Mockingbird. Austin, TX: U of Texas P.

Lodge, T. (2010). The Everglades Handbook: Understanding the Ecosystem. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.