On last weekend’s scouting expedition to western Palm Beach County we found a new life bird for me: Upland Sandpiper. Finding a life bird is getting to be a rarer and rarer event. Now that my Florida list is over 250 species (nowhere near the “full count” of 500+ that have been documented in the state), it takes a bit of effort to get a new one. For example, I’m expecting to have to canoe the mangrove islands down in the Everglades to get Mangrove Cuckoo (unless I get lucky on Lignumvitae Key). And if I want to see a Brown Noddy, I’ve got to get on a boat and head out to the Dry Tortugas.

So each new bird deserves a bit of a celebration, and that’s what today’s post is: a celebration of Bartramia longicauda, formerly Bartram’s Sandpiper, now Upland Sandpiper. It was first described by Johann Matthäus Bechstein in 1812, and only slightly later by Alexander Wilson in volume 7 of American Ornithology as Tringa bartramia; by the time Wilson’s description was picked up for volume 3 of the 4-volume 1831 Edinburgh edition of American Ornithology, [the edition Google has digitized, which is the only one I can access] it had become Totanus bartramius.

My first encounter with this species was on a sod farm off County Road 880 in western Palm Beach County. Wilson’s first encounter with the bird was near the botanic gardens of his “very worthy friend,” William Bartram, “on the banks of the river Schuylkill.”

If you read that last sentence carefully, or if you follow the link to the Google books scanned version of Wilson’s text, you’ll see that Wilson has laid a pretty trap for us. He’s found a new species of shorebird, and he immediately links it to water (the Schuylkill river) via Bartram’s gardens. But he never actually says that he found it near the river. He found it “near” the gardens, which are “on the banks” of that impossible-to-spell-without-triple-checking river in Pennsylvania.

He’s just having a little fun with us, is all; he goes on almost immediately to distinguish this shorebird’s habitat preferences from its congeners (well, Wilson considered them congeners, although now we place this bird in its own genus, Bartramia) in terms that most birders and field guide authors haven’t seen fit to change very much at all.

In the first place, this is a “grasspiper,” not a sandpiper:

Unlike most of their tribe, these birds appear to prefer running about among the grass, feeding on beetles, and other winged insects. (86)

And furthermore, this is the shorebird that you won’t find on the shore!

Having never met with them on the sea shore, I am persuaded that their principal residence is in the interior, in meadows and such like places. (86–87)

I would say that an overgrown sod field counts as a meadow, wouldn’t you?

Even John James Audubon, who delighted in contradicting Wilson whenever he could doesn’t dispute this part of the bird’s description; the most famous American ornithologist describes it in his Birds of America as “the most truly terrestrial of its tribe with which I am acquainted.”*

Wilson called the bird Tringia [sic] bartramia, while Bechstein called it Tringa longicauda; it is Bechstein’s specific epithet that has won the day. Wilson’s choice to honor Bartram has been respected, though, by placing it in the single-member genus, Bartramia. This is an excellent example of respecting tradition while revising it to be more descriptive: while the genus honors the original namesake of the bird, the specific epithet describes it: longicauda, long-tailed. And it’s true; compared to other sandpipers, Upland Sandpiper does have a fairly long tail; look how far past the wingtips the tail extends in this detail from Naumann, Naturgeschichte der Vögel Mitteleuropas (Natural history of the birds of central Europe):

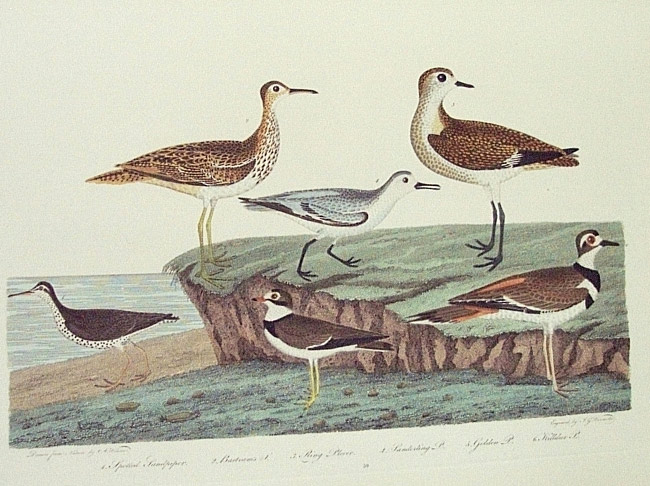

You can also see it in Wilson’s plate from American Ornithology:

The plate shows clockwise from top left, Upland Sandpiper, Sanderling, American Golden-Plover, Killdeer, Semipalmated Plover, and Spotted Sandpiper. Given its companions in this photo, which would rarely be seen together in life (the beach-loving Sanderling right next to the prairie-dwelling Upland Sandpiper?), it might seem that habitat preference got trumped by the need to have this bird appear on a plate somewhere. In fact, though, it’s probably the Sanderling who got crammed onto this plate at random; the others appear to be fairly near their preferred habitat, given that it appears on the grass with the appropriately placed UPSA and AMGP.

Older naturalists like Wilson and Bechstein seemed to have placed all shorebirds in the genus Tring[i]a; the specific epithet honors Wilson’s “very worthy friend, near whose botanic gardens, on the banks of the river Schuylkill, [Wilson] first found it.” The new standardized common name, upland plover, foregrounds this habitat preference in a way the previous name, for all its lore and association with the great naturalist William Bartram, son of the great botanist John Bartram, does not. (A.C. Bent begins his 1929 account of Upland Plover with the invocation “Let us be thankful that this gentle and lovely bird is no longer called Bartramian sandpiper.”)

Wilson also points out, perhaps with unconscious irony, that, when he saw three or four of them together that first time near Bartram’s gardens, “they seemed extremely watchful, silent, and shy, so that it was with extreme difficulty I could approach them” (86). On the next page, the reader can infer why they are so hard to approach:

They are remarkable plump birds, weighing upwards of three quarters of a pound; their flesh is superior, in point of delicacy, tenderness, and flavour, to any other of the tribe with which I am acquainted. (87)

Hmmmm…. A plump, tasty bird that’s also watchful, silent, and shy. I wonder why?

Market hunting of this bird reduced its numbers substantially in the 19th century; A.C. Bent comments that

The upland plover is, or was, a fine game bird. Over 40 years ago, in my younger shooting days, these birds were still fairly common in Massachusetts, but it was no easy job to make a fair day’s bag; it meant tramping many miles over rolling, or hilly pasture lands, where the wary birds rose at long range and flew swiftly away for a long distance.

Bent also cites Forbush (1912) on the market hunting pressure on this bird in the U.S:

About 1880, when the supply of passenger pigeons began to fail, and the marketmen, looking about for some other game for the table of the epicure in spring and summer, called for plover, the destruction of the upland plover began in earnest. The price increased. In the spring migration the birds were met by a horde of market gunners, shot, packed in barrels and shipped to the cities.

Bent cites Wetmore and others on the hunting going on in the South American wintering grounds as well, but you get the idea: market hunting in the past, combined with habitat destruction now, has really given this poor prairie bird a tough row to hoe. The latest field guide I have says this bird’s numbers are “declining, especially in East.”

Which makes it all the more exciting (to me) to have seen, just like Alexander Wilson, “three or four in company” out at 6-Mile Bend. We had stopped at this field earlier that morning, when there were many more birds present, but either we were distracted trying to sort through the various Killdeer, dowitchers, and other species, or the birds simply weren’t there. They were in an overgrown field, whereas their compatriots were in the nice short sod in the foreground, so it’s quite likely that we simply overlooked them earlier.

Expert opinion in the matter has said that, at least on migration here in Palm Beach County, they usually aren’t seen early in the morning, so we can choose the more flattering explanation for why we missed them just after dawn: they weren’t there! Isn’t that much nicer than saying that we just plain missed seeing them? It might even be true.

Next time I’m out in the sod fields, I’m looking for Buff-breasted Sandpiper.

* Audubon does, though, make a point of mentioning that they do appear in large flocks: “It has been supposed that the Bartramian Sandpiper never forms large flocks, but this is not correct, for in the neighbourhood of New Orleans, where it is called the “Papabote,” it usually arrives in great bands in spring, and is met with on the open plains and large grassy savannahs, where it generally remains about two weeks, though sometimes individuals may be seen as late as the 15th of May. I have observed the same circumstance on our western prairies, but have thought that they were afterwards obliged to separate into small flocks, or even into pairs, as soon as they are ready to seek proper places for breeding in, for I have seldom found more than two pairs with nests or young in the same field or piece of ground.”

References

Audubon, J.J. (1832) Ornithological Biography. The companion text to the plates of his Birds of America. The National Audubon Society has made available a digitized version of the text, with accompanying (tiny!) images at http://web4.audubon.org/bird/BoA/BOA_index.html

Bent, A.C. (1929). Life Histories of North American Shorebirds. Part Two. Smithsonian Institution United States National Museum Bulletin 146. Reprinted New York, NY: Dover Press, 1962.

Floyd, T. 2008. Smithsonian Field Guide to the Birds of North America. NY: Harper Collins.

Wilson, A., & Bonaparte C.L. (1831). American Ornithology; or the Natural History of the Birds of the United States. Ed. Robert Jameson.