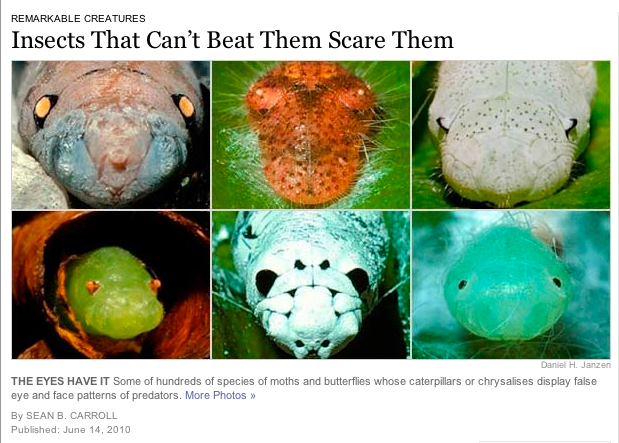

Sean Carroll, writing in the New York Times, posted a very interesting article yesterday about an ecosystem in Costa Rica that has developed thousands of caterpillar species: more from this one small area (77 square miles of Costa Rican rainforest) than in all of North America. Among the species described in this three-decades-long research project are hundreds of caterpillars (and even chrysalises) that appear to have evolved a deterrence against predation: eyespots.

This strategy is not new to science: in the 1860s, Henry Walter Bates developed a hypothesis of mimicry among animals whereby tasty treats like caterpillars and butterflies experience selection pressure to resemble other species that are distasteful or poisonous. In other words, Batesian mimicry describes what looks to be a free ride: when a palatable species evolved to resemble an unpalatable one, they enjoy protection from, say, birds that have previous experience with the noxious species. The only cost here is the evolutionary cost of changing your appearance enough to resemble the noxious form.

Another famous type of mimicry was described by Fritz Müller in 1878. In Müllerian mimicry, two poisonous species resemble each other and gain survival benefits from the increased advertising effect. Predator species benefit as well, since they don’t have to waste time trying to eat those unpalatable species that resemble each other.

Eyespots are a different defense mechanism among the adults of some butterfly and moth species, and are apparently much more susceptible to rapid evolution. Most eyespots are on the wings, far away from the vulnerable abdomen, and they appear to concentrate predation attempts on those areas. The idea, which seems to be borne out by experience, is that the prey species can afford to have their wings clipped if it means they can fly away relatively undamaged. So the eyespots function as distractors.

But in these caterpillars in Costa Rica (hundreds and hundreds of species, remember), the eyeballs serve a more direct defensive purpose. They make the innocuous, and potentially tasty, caterpillars, look more like dangerous, and potentially deadly, snakes. In fact, some species even rattle! As Carroll writes,

[T]he distinct behavior of many caterpillars when handled underscored that the whole game was to startle the many species of insect-eating birds that foraged in the dry, cloud and rain forests of the conservation area. Some eye patterns became visible only when the caterpillars were molested and expanded part of their body, and some large specimens wriggled and rattled like snakes.

Dr. Janzen and his colleagues estimate that a typical foraging bird might encounter tens to hundreds of false-eyed bugs each day. It is unlikely that a bird encountering such a spectrum of patterns could learn to discern which specific ones were safe and which were not, especially when one mistake would mean its demise. It would be better to leave suspicious items alone and to quickly move on.

Here’s a screenshot of the photo collage of Costa Rican caterpillars that accompanied the article; there’s an entire slide show that you really should visit for yourself. These creatures are bizarre and gorgeous:

One of the take-aways from this study was relatively new, at least to me: mimicry can operate on what looks to be a hard-wired level. These caterpillars do not resemble noxious species, nor are they themselves noxious (as far as the article goes; I haven’t reviewed the original research). The eyespots provide at most a general type of resemblance, nothing like the specificity described by Bates or Müller. As Carroll puts it, “The variety of patterns suggested that the bugs [sic!] do not have to match exactly the appearance of any particular predator for the ruse to work”:

[W]hen it comes to a deadly encounter with another species, there may be no second chances, no opportunity for learning. Hence, natural selection would favor instant recognition, and hard-wired rapid responses, in a close encounter with potential danger. Harmless creatures that evolved some general resemblance to the variety of creature features to be avoided (eyes, scale patterns) would then gain some protection.

If you do click on through to the slide show that I linked to above, though, you’ll see some species that certainly match my preconceived idea of a predator, particularly the beastie in slide 1 of 20 (not pictured in the screenshot above). My own response to this mimic proves the success of the strategy, at least for a generalized predator like me, in the absence of experience with this particular species: That looks like a snake! Best not to mess with it! (Hard-wired response in a primate to snakes? Maybe…)