When my eyes snapped open at 4:30 Thursday morning, it took me a minute to remember why it was a good thing, rather than a bad thing. I was tired, having stayed up late getting everything ready to try to view the scar arising from the recent impact on Jupiter. For the first time in two years, I had set up the CG-5 mount and tripod for my 200mm SCT. I chose what looked like an acceptable viewing location in the back yard, did a rough alignment so that the auto-align process would go more smoothly in the morning, then carefully wrapped the setup in a tarp to avoid problems with dew.

All that remained was to carry the scope out to the mount in the morning and go through the alignment steps to get ready to observe. If I could do those two things without dropping anything or stubbing my toes too hard, I would have a decent chance of capturing some digiscoped shots of the event. And, as you can (sort of) see from the images below, I enjoyed some small measure of success (click on any of the pictures for a larger version).

Since the tripod was already set up and roughly aligned, it only took about 15 minutes to cart the scope, battery pack, and eyepieces out to the tripod, set them all in place, and run through the steps to get the CG-5 goto mount computer aligned:

- Balance the scope

- Line up the polar and equatorial axes on their respective index marks

- Turn the handheld controller on

- Find a few visible bright stars that also happen to be in computer’s database

- Slew to each star in turn

- Center star in finder scope

- Align star in telescope eyepiece

And hey presto! No further need to mess with the mount! Ain’t computers grand? (Now if only the mount didn’t sound like a coffee grinder when in motion!)

Given my restricted viewing area, it was hard to find stars that (a) existed in the auto-align setup program, (b) were unobstructed by trees or other vegetation, and (c) I recognized by their “proper” (generally Arabic) name. Seriously. I’m familiar with Altair, but Alnair? I don’t know that one, at least not at 4:30 a.m. after two years of essentially no observing time whatsoever. Time to fish out my Kunitzch and Smart and get reading! (And boy, am I glad Sky and Tel decided to issue a new edition; the first edition is almost impossible to come by. I know of one person who has it, but no one else.)

Eventually, though I was able to coax the machine into giving me Vega, Albireo, and Capella as guide stars, and got the mount aligned relatively easily. (Or so I thought. For some reason, although the align was successful, it didn’t slew to Jupiter very well; it wasn’t even in the finderscope, let alone my widest field eyepiece. I guess having no dry runs after a 2-year astro-layoff really reduces your ability to work in the field!)

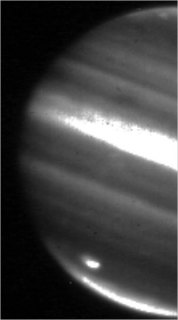

Another thing I discovered is that it’s quite hard to control the exposure on a point-and-shoot camera in the dark. That’s one of the things I’ll need to remember to do the night before if I ever pull a crazy stunt like this again. The image below was taken before I managed to get the exposure settings right:

Notice how overexposed the image is? But at least you can see that we have, from upper left to lower right, Io, Callisto, Jupiter, Europa, and Ganymede. What you can’t see is that Callisto was in the middle of a shadow transit; the brilliantly crisp view through the eyepiece made itself apparent even to my sleep-heavy eyes.

The next image shows that it’s also hard to know when you’ve got the exposure settings right; the display on the back of my Coolpix 5100 can’t handle images with such strong contrast. I had thought that the image below was overexposed, so I went ahead and kept “correcting” the exposure, so all my remaining 6 or 7 images are almost completely black! This, and one other, slightly less successful one, is the only “in-focus” image from the session. If you look closely, you can make out the shadow transit of Callisto, but you can’t see the “bruise” from the recent impact, although it was visible in the eyepiece when the seeing was clear.

Since I thought I’d undershot the settings on the camera, all of my next shots were wasted, because I overshot, trying not to overexpose the image. Below are two of the “best” of the images I took with what I thought were the correct settings based on the back-of-camera display. As you can see, my impression did not match the reality! I had to tweak the “levels” sliders pretty hard in my image processing software to get this much data out:

The view through the eyepiece was much crisper and more intelligible than these shots might lead you to believe. Jupiter’s bands showed quite clearly, and if I remembered how to describe them, I would be able to tell you all about the detail that was visible from time to time. As I write this piece, it becomes increasingly obvious to me why the best observations of the planet come either from frame captures taken by webcams, where you can stream image after image to get the best seeing, or through patient sketching with pencil and paper. Either technique allows/requires you to understand what you’re seeing, which leads to being able to see more.

Thursday morning, the image through the eyepiece would be clear for a couple of seconds at a time, then it would waver as low-level heat shimmer wafted through the line of sight, making me check to see if water was actually running over the eyepiece. It wasn’t. It turns out that my carefully chosen site was right over the air handler of my neighbor’s a/c unit, which kicked in about halfway through the session, totally destroying the seeing. (Yes, most houses in my neighborhood need to have the a/c running before 5 a.m.!)

Here are a few images from the various space agency websites of what I should have been seeing. None of these shots, of course, are possible with my amateur setup, although some more practiced (and, I assume, better funded) amateur astronomers are getting fabulous results.

This is the shot the NY Times ran yesterday, courtesy of NASA; it was taken in the infrared:

This is another infrared image of the scene, processed quite differently. It comes from the Keck Observatory release about the situation; it shows Earth and the new feature in correct relative size:

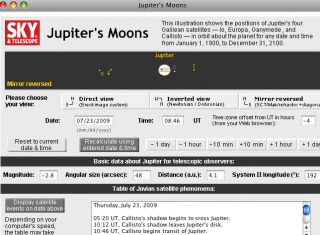

And, for those of you wondering which moons are visible in my photos, here is what Sky and Tel thought I should have been seeing:

I had the app set for SCT views, but you’ll notice that my image appears to be mirror-reversed from this one. My shot actually resembles the “erect image” view much more closely than the SCT view. I’m still not sure why this should have happened…

The entire session, from opening my eyes to returning to bed, lasted about an hour. I would have spent more time on it, but for two things: (1) I thought that I had captured some good images (next time, feed them directly to a computer to check at the scope!), and (2) the mosquitoes were eating me alive. Wearing a t-shirt, thin sweats, and crocs with no socks is no way to slip under the radar of these thirsty mamas!

So yet another episode of amateur investigation into the wonders of nature is curtailed by another of the wonders of nature. Seems like a theme here in SoFla…