I have to say that, despite the recent impact visible on Jupiter dominating the geeky side of the news these days, I’ve drifted a ways from my astronomical roots since last March. (Any guesses as to why?) But with my recent visit to the newly restored Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles (to be detailed in a post soon–maybe even a guest post!) to inspire me, I was poised to take advantage of Wednesday morning’s incredible gift from the boy: a leisurely 6 a.m. wake-up, followed by a 6:15 a.m. back-to-bed!

So as I strolled out to get the morning paper and just happened to glance up at a SoFla sky that also just happened to be clear, I was able to notice the bright beacon of Venus over in the east:

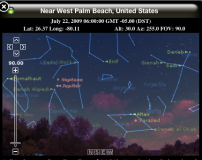

matched by a corresponding glow from Jupiter over in the west:

And I actually had 2 minutes to run inside and get my binoculars to check them out briefly!

Through binoculars, at a paltry 7x magnification (the best I can manage handheld without–hint hint!–image-stabilized binoculars) was glimpse Venus’s phase, and just barely make out one or two of the Galilean moons against the rapidly brightening sky–just enough to convince me that I was really looking at Jupiter, not Saturn. (That alone should tell you how little stargazing I’ve been doing lately–I had no idea where the planets were “supposed to be” at 6:15 Wednesday morning, so I was very pleased to be able to tell that the super-bright object in the east was obviously not round, and the slightly-less-bright one in the west had the Galilean moons…)

Venus appeared to be about half-full (I checked the ephemerides, and I wasn’t too far off, as it’s supposed to be around 66% on Wednesday, July 22). Being an inferior planet, it is able to run through almost the complete cycle of phases, as Galileo observed in 1610 (although he didn’t publish until 1623), whereas Jupiter, being a superior planet, rarely exhibits any noticeable phase effect.

I mean phase in the astronomical sense, of course, not a mood or developmental stage–as in “It’s just a phase s/he’s going through; it’ll pass.” Ironically, though, by definition, the phase will pass! I wonder if the looser meaning of phase has any of the sense of the ineluctable carried by the technical definition? This technical meaning is well defined in Bakich’s Cambridge Planetary Handbook as “the percentage of illumination of the Moon or other solar system object at a particular time during its orbit.”

Hmmm. Since I’m defining phase, I might as well define how I’m using inferior and superior, as well, for those who were too lazy or security-conscious to click through the links earlier… By “inferior” and “superior” I do not mean any exaggerated respect toward the king of the gods, nor any disrespect toward the goddess of love and beauty. The planets that these gods represent (and yes, I mean that: the planets came first, the gods followed, not the other way around) lie in celestial orbits, and these relatively fixed paths are what determine their inferiority or superiority, not any intrinsic or ascribed quality of character or composition. Venus’s orbit lies inside that of Earth’s. It is, then, by definition, an inferior planet. And because Jupiter lies outside Earth’s orbit, it is defined as a superior planet.

The inferior planets, then, (Venus and Mercury) never appear far from the sun; they exhibit phases similar to those of the moon, ranging from very small crescents to round orbs. The superior planets (Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn for naked-eye observing, and Neptune and Uranus if we throw in telescopes–Pluto, by infamous decree, no longer counts) can appear anywhere in the night sky along the ecliptic, and exhibit only minimal, if any, phase effect.

The maximum phase for Mars is 94%, if I recall correctly (actually, I’m off by a good amount: according to Fred W. Price in the Planet Observer’s Handbook, “The fraction of the visible disc illuminated may decrease to 84%” (134) when Mars is at quadrature; that is, when it is at it’s “phasiest.”). Jupiter, being so much farther from Earth than Mars, exhibits substantially less phase effect; it’s so slight that not even Price deigns to quantify it, although I’m fairly sure I’ve noticed it, or had it called to my attention at an observing session at least once or twice in my observing career. (Now if only I’d been keeping a good observing log, as one is supposed to do, I could look that up…)

We’re more likely to notice Jupiter’s oblateness (the difference between its equatorial and polar diameters) than its phase. Jupiter’s polar diameter is only 93% of its equatorial diameter, for an oblateness of .06481 according to Bakich. Mars is much rounder, with an oblateness of only .00519; Earth is rounder still, with an oblateness of only .00335.

All the numbers aside (really, what good do the numbers do to handheld binocular astronomy in a fairly bright morning sky?), it felt good to reconnect to this rich field of intellectual engagement, even if it was only for a minute or two. Maybe I’ll even be able to do it again; I understand that Jupiter’s new cloud bruise will be visible in my neck of the woods around 5 a.m. today. I’ve set up my equatorial mount, checked that the controls still work (I hadn’t so much as plugged it in since 2007!), and hope to heck I can wake up in time…

[UPDATE: I was able to wake up in time; terrible pictures and description to follow. Well, the pictures are terrible. I’m hoping the description will make up for it…]